The year is 1862. The Homestead Act is born under the guiding hand of the Union government, granting any head-of-house, adult, or intended citizen who’s never borne arms against the United States the opportunity to claim 160 acres of public government land, provided they live on it for five years and pay the filing fee. Manifest destiny is more than just a political philosophy. It’s a way of life.

Fast forward to 1882. Joseph Hodges and John Schanck, spurred on by the dream of owning land in the West, travel from Illinois to the Dakota Territory, loaded up with lumber for a barn and claim shanty along with a team of mules and horses. The railroad takes Hodges and Schanck as far as De Smet, located in present-day Kingsbury County, SD. Established in 1880, De Smet greets the two men with nothing more than the bare accessories that come with the word town, including a general store, bank, hotel, saloon, newspaper, church, and lumberyard.

Hodges and Schanck file adjoining claims for homesteads of 160 acres lying about 17 miles northeast of De Smet. If prospective homesteaders haven’t been to the land office to file their claim yet, many reserve their claims by laying four poles together to form the beginning of a building or by digging a hole two to three feet deep to indicate a well is being built. These methods serve as temporary claims until the land is filed on. Without immediate action claims are often lost to other land-hungry settlers within a few days.

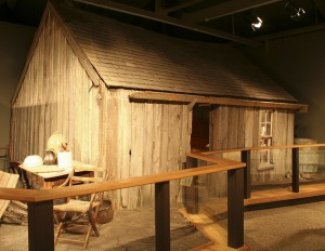

Gaining a title to the homestead means building a dwelling on the claim as an improvement and proof of residence. With their Illinois lumber hauled out to the Dakotas by train, Hodges and Schanck build a claim shanty on the line dividing their property. One building counts for both claims. While not technically legal, they add a partition in the shanty and an extra door to create separate “dwellings” in order to comply with the regulations.

Claim jumpers are a threat to the peace of homesteaders. Often during the frigid winters homesteaders move to town or even out of the territory for a few months to take up jobs and earn extra money. The remaining homestead is left unattended, vulnerable to theft. Newcomers passing through the area may take up residence in the empty shanties, some through greed, others through laziness or ignorance. Claim jumpers are never a welcome sight. Surrounding neighbors often act in their fellow homesteader’s best interests and many times do whatever it takes to get rid of the trespasser, whether by calling on the law or taking matters into their own hands.

The average claim shanty isn’t much to look at. According to Laura Ingalls Wilder, “It was one tiny room, boarded up and down, one way sloped roof which looked like half a little house.” (Wilder, 1939)

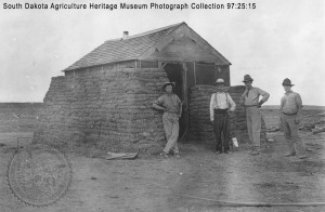

Claim shanties aren’t always constructed out of wood. While wooden shanties are often preferred because they’re quick and easy to build, sod houses are also an option. Built straight from the earth, “soddies” are made from blocks of prairie sod.

While soddies make a solid and reliable shelter, wooden claim shanties aren’t known for being sturdy. Shanties are temporary living structures. Until enough resources can be pooled together to build a permanent home, a shanty is quickly thrown together as a shelter to fit the Homestead Act’s requirements.

Claim shanties can’t always be relied on to remain where they’re built. As Edith Eudora Kohl writes, “It was a typical homestead shack, about ten feet by twelve feet containing only one room and built of rough foot wide boards. It had obviously been put together with small concern for the fine points of carpentry and none whatever for appearance. It looked as though the first wind would pick it up and send it flying through the air.” (Kohl, 1938)

While that shanty looked like it couldn’t withstand a blustery wind gusting across the prairie, other shanties actually met that fate.

“A claim shack might disappear overnight in a high wind.” (Anderson, 1977)

And as found in the Dakota Farmer, “On this claim, at first, a small shanty had been built of boards, four sides and a roof without any floor other than Mother Earth provided, but this shelter which sat upon the prairie like an umbrella was soon blown down, flattened out and scattered by the wind.” (Dakota Farmer, 1881–1979)

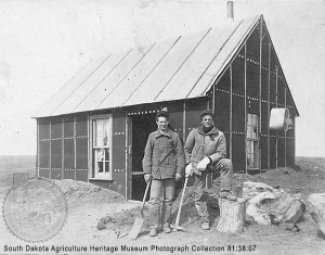

The wise homesteaders anchor down their shacks with wires running over the roof to stakes rammed into the ground. Especially with the howling winds of winter, claim shanties can be insulated and reinforced with a mixture of horse manure and straw.

“This was not as disagreeable as it sounds, resulting in a frozen impermeable protective mass, odorless so long as it remained frozen.” (Lewis, 1979)

Tar paper is also used to block out the wind, rain, and snow. According to Richard Cropp, “what really held the tar paper on and kept the shanty from blowing away was the sod from the fire break plowed around the house. This was piled up neatly to the eaves. Next spring we found that the sod on the north side raised any amount of edible mushrooms.” (Cropp, 1981)

With little to decorate, homesteaders often whitewash the inside of claim shanties or plaster the inner walls with newspapers. According to Hodges’ son Harry, “the claim shanty walls were papered with copies of De Smet papers and those of his old home at Wyoming, Illinois.” (Hodges Family Collection)

Hodges’ and Schanck’s shanty, standing just 12 by 16 feet, endured the testing of pioneer trials on the South Dakota prairie and still remains today, now on exhibit at the South Dakota Agricultural Heritage Museum. It remains as a testament to the settlers who had a vision and remained to build a new life despite the difficulties that came their way.

by Erin Beck, Museum Intern 2014

Sources

Anderson, Iola M. The Singing Hills. Argus Printers. Stickney, S.D. 1977.

Cropp, Richard. “My Life and Times as a Six-Year Old Homesteader.” Selected Papers of the First Nine Dakota History Conferences 1969–1977. Dakota State College. Madison, S. D. 1981.

Dakota Farmer. Vol. 1–99, 1881–1979.

Dick, Everett. The Sod-House Frontier. Johnsen Publishing Company. Lincoln, Nebraska. 1954.

Hodges Family Collection.

Kohl, Edith Eudora. Land of the Burnt Thigh. N.Y. Funk and Wagnalls Co. 1938.

Lewis, William R. An Historical Momento, Lake Preston Centennial 1879–1979. Lake Preston Times. Lake Preston, S.D. 1979.

Parker, Donald Dean. History of Our County and State (Kingsbury County). South Dakota State College. Brookings, South Dakota. 1961.

Wilder, Laura Ingalls. On the Banks of Plum Creek. N.Y. Harper and Roe. 1939.

Yost, Josie Lee. A Summary of Homestead House Types in South Dakota 1860–1910. 1983.