Wokini: A Morrill Obligation to Create a New Beginning

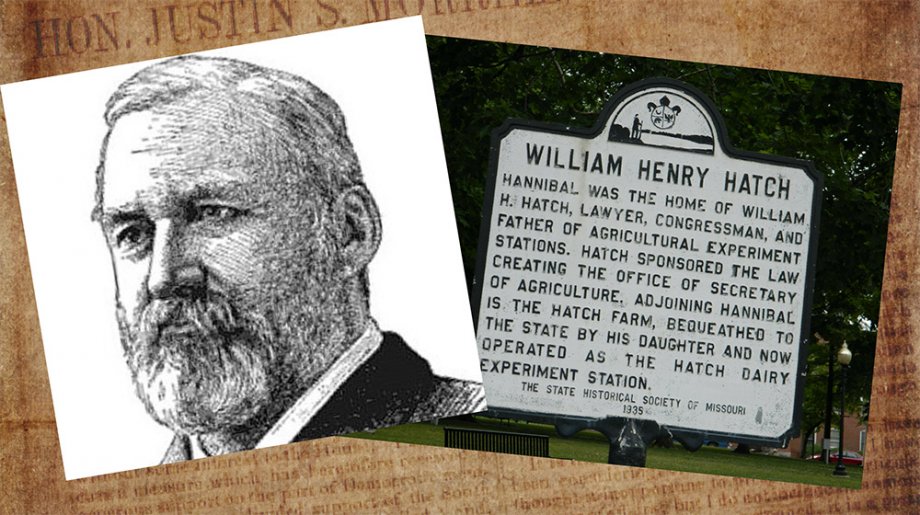

President Dunn presented the Hatch Lecture Nov. 10, 2019 in San Diego.

OPENING REMARKS

Thank you for your kind introduction, Under Secretary Hutchins. I am extremely humbled by this recognition and would like to thank those involved for me being here today.

William Henry Hatch was a lawyer, Congressman from Missouri, and a farmer. As you know, his leadership created Agricultural Experiment Stations, which propelled research to the unbelievable heights we have reached today. But just as importantly, initially, it helped enrollment and improved faculty training and expertise throughout the young land grant colleges across our nation. It provided those struggling Land Grants with renewed purpose. It changed the world.

Today, Agricultural Experiment Stations continue to solve the world’s complex issues and find ways to feed a growing global population, tackle climate change and define sustainability.

My professional path benefited tremendously because of the vision and leadership of William Henry Hatch. And so, I am extremely honored – and privileged to present the 2019 William Henry Hatch Lecture.

INTRODUCTION

Over time, courageous and visionary leaders changed the path of human history with the passage of the Morrill Act of 1862, the Hatch Act of 1887, the second Morrill Act of 1890, the Smith Lever Act of 1914 and the Equity in Educational Land-Grant Status Act of 1994.

Collectively, they created what we have come to know, and treasure, as the Land-grant system of education, research and extension. During the floor debate of the 1862 legislation, Justin Morrill explained its goal this way: “The bill proposes to establish at least one college in every state, upon a sure and perpetual foundation, accessible to all …”

While I fully recognize there are imperfections, since the passage of those legislative landmarks, the benefits of higher education have unleashed the human potential of millions of individuals for the betterment of themselves, their families, communities and our economy, society and democracy.

For the last 132 years, through the power of Agricultural Experiment Stations, unbiased, science-based research has tackled the challenges and explored the opportunities of the day, and lifted the standard of living and increased the life expectancies of literally hundreds of millions of people in the United States and around the world.

For over a century now, the Cooperative Extension Service has systematically sought to challenge the ivory tower of education to extend its boundaries, and its benefits, to the people and communities beyond its campus borders.

From South Dakota State University, 90,000 alumni from every state in the nation, and countries across the world, have graduated and thrived, including a Nobel Poet Laureate.

Hundreds of thousands of children have benefited from our 4H programs.

Literally thousands of advanced crop varieties of have been released to fortify our state’s No. 1 economic engine, agriculture. It is a glorious story of hope, achievement and success.

BODY

Archimedes, one of the great scientists and mathematicians of ancient Greece, once said: “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.”

As you know, there are four key components to the power of a lever. You need the lever, fulcrum and load described by Archimedes. But you also need a force.

What a powerful metaphor for the Land-grant system … Archimedes’ long lever as education, research and Extension. The children of toil as the load that needs to be lifted. The force—the celebrated pieces of federal legislation I just mentioned.

But what represents the fulcrum in our metaphor?

In the 1862 legislation, in order to provide a “sure and perpetual foundation,” as called for by Justin Morrill, the federal government granted 30,000 acres of land for each member of congress when the mantel of Land-grant status was placed upon one of their state colleges. And when the Agricultural Experiment Stations were started, a state received an additional 40,000 acres of land to support them.

And so, land was the fulcrum on which the long lever of education and research were placed, and with the incredible force of Justin Morrill and William Henry Hatch, we have moved the world. Archimedes would be proud.

But of course, as with everything, there are multiple perspectives from which to view this remarkable story.

In all of the presentations I have heard about the Land-grant system, the two questions that I’ve never heard asked, let alone answered, are quite simple:

- Where did the land come from?

- Whose land was it?

The answers to those questions for the Land-grant university for which I humbly serve as president are quite simple.

With the enabling act of statehood in 1889, the state of South Dakota received 160,000 acres of land from the federal government for the benefit of what is now South Dakota State University, which was designated the state’s first Land-grant college and Agricultural Experiment Station.

The land was made available with the passage of the Dawes Act two years earlier, which broke up the Great Sioux Reservation. Land that had been promised to the Lakota people in the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. So….. the land that has acted as the fulcrum for SDSU’s Land Grant lever for 140 years, was someone else’s land.

In 1921, my mother, Sarah, was born on the Rosebud Indian reservation in south central South Dakota. My grandfather, Claude, was a member of the Rosebud Sioux tribe. My grandmother, Hattie, was from Nebraska. They lived on the treeless prairie and attempted ranching.

My mother was born in the humblest of conditions. My grandmother reminisced how my grandfather would bring home prairie chickens and grouse that he had shot, and that is all they had for supper.

By 1930, the ag economy sank into depression. Out of desperation, my grandparents moved with my mother and her two brothers to Sioux City, Iowa. My grandfather worked nights in the stockyards, unloading train cars that hauled thousands of cattle and hogs. He did this miserable work in all conditions: rain, snow, the cold of winter or the heat of the summer. He also worked Sundays because he could earn an additional 5 cents an hour.

As he told me his story, it brought forth the brutal images of the meat-packing industry described in the famous novel, “The Jungle,” by Upton Sinclair.

Since the earliest days of the cultural clash between European settlers and Native Americans, alcohol has been, and continues to be, a scourge for native people. The tragic, crushing, ruinous damage to thousands and thousands of lives is incalculable.

Sadly, my mother’s family was not spared. Two of her brothers were alcoholics and chose to violently end their own lives, devastating the family.

Out of poverty and darkness, and during the Great Depression, somehow, someway, my little brown-eyed, brown-haired mother, all 5-foot-1 of her, found her way to Iowa State University.

She was a member of the Tri-Delt sorority and had a wonderful time in college. She graduated in four years with a degree in home economics.

After graduation, and to support the war effort, Mom took a “Rosie the Riveter” type job in Akron, Ohio, making tires for Army vehicles. The tires were bigger than she was. She met my dad in college and they married after he got out of the Army Air Corps following World War II.

Her education, experiences and opportunities at our sister Land-grant university lifted her up, along with our entire family. Her children were the clear beneficiaries of her knowledge of nutrition and early childhood development.

She was a wonderful mother. She woke up early every morning on the sunny side of life.

I am certain that each of you have compelling stories of your families overcoming similar conditions. However, keep in mind that when my mother Sarah was born, because she was a Lakota, she wasn’t a citizen of the United States.

I understand that Sarah’s life accomplishments may seem modest in comparison to those of you in the audience this morning, but when this young woman from the Rosebud graduated from college, less than 4% of the women in America had a college degree.

Sadly, I don’t know the answer to the “how on Earth?” question that this story elicits.

At that time, the lever and fulcrum were not typically positioned to help people like my mother. But clearly, gratefully, the fulcrum at Iowa State University was re-positioned for my mother, and she was lifted up.

She died from cancer long ago, near where she was born, on the beautiful Rosebud.

Sadly, the current landscape for American Indians in South Dakota is not much different from what it was nearly 100 years ago when my mother was born.

Members of the nine tribal nations in South Dakota make up 9% of the state’s population. If you haven’t seen “third-world poverty,” you don’t need to have to travel far. Come to South Dakota and I will take you to Pine Ridge or Rosebud.

Unemployment rates exceeding 80% are not unusual, but they crush the human spirit.

While frequently discussed as a federal or “Indian” problem, currently 33% of the male population, and 63% of the women’s population in South Dakota’s penitentiaries are American Indians, costing our state tens of millions of dollars each year.

Reservation youth have the highest rates of alcohol-use disorders of any racial group in the country.

Suicide is the second-leading cause of teen deaths.

Obesity levels are double the national average. At the same time, these regions are classified as food deserts by the USDA.

Educational attainment levels are very low and one out of 10 people, 12 and older, become victims of violent crimes annually.

There is very little understanding or appreciation for the historical trauma inflicted upon the Lakota and Dakota people of South Dakota. There isn’t even a permanent marker memorializing the site of the Wounded Knee Massacre.

There is also very little understanding or appreciation for the history, culture and community of the Lakota and Dakota people.

Sadly, remnants of the Manifest Destiny survived the 19th and 20th centuries and racism, both overt and covert, remain.

Efforts to help, while seemingly well meaning, are fraught with tokenism, self-righteousness, insincerity, lack of respect, assumptions and bias.

SDSU’s history in serving these people is very poor.

Less than 2% of our student population self-identify as American Indian compared to the 9% of our state’s population. Graduation rates are abysmal.

To be fair, it is not for a total lack of good intentions. Over the years, a few dedicated faculty and staff have tried to make a difference. However, success has been limited by the reliance on short-term grants and efforts have proven to be unsustainable.

But still, honestly, few faculty and staff have any historical or cultural sensitivity or awareness.

And to be blunt, as I reflect on the many historic accomplishments of South Dakota State University that I mentioned earlier, I can’t point to a single one that positively impacted the people of the nine Dakota and Lakota tribes of South Dakota in truly systemic ways.

When I considered applying to be the 20th president of my alma mater, I was struck with the reality that if I got the job, I would have the bully pulpit, and the budget, to do something about this festering, lingering and, I believe immoral, situation. I knew there would be tremendous political risks on campus and across our state.

But my mother’s voice echoed through my thoughts, quietly, as was her way, asking me: “So if you become president, what do you think you could do to help?”

Thankfully, C.S. Lewis’ wonderfully provocative statement of grace came to mind. “You can’t go back and change the beginning, but you can start where you are and change the ending.” It emerged as a guiding principle for me.

When I became president of SDSU, Wokini, which means “a new beginning” in Lakota, came to life. Its purpose is twofold. First, to support citizens of the nine Tribal Nations in South Dakota interested in gaining access to the benefits of higher education and advancement opportunities to benefit themselves, their families, communities and tribes.

And secondly, to enhance research, outreach and service collaborations and partnerships with tribes and tribal colleges.

After much conversation with many leaders on campus and across Indian Country, five central strategies emerged.

The first is to make a land acknowledgement statement explaining and owning our past.

The second is to commit to use the annual flow of resources from our Land-grant land to benefit the heirs from whom the land was taken so long ago.

The third is to build a new American Indian Student Center in the heart of campus.

The fourth is to provide meaningful, life-changing scholarships to American Indian students.

And the fifth is to leverage the base funding from our Land-grant land with federal funding, grants and private gifts.

How will we measure success?

That will come when the population of American Indian students at SDSU is proportional to South Dakota’s American Indian population and when the success of those students equals, or exceeds, that of the general student body.

We have pledged that “accessible to all” will not be just an old, quaint notion enshrined in a historical document, but a living commitment.

How will we measure success?

It will be when Tribal Nation building is a core part of our university’s activities.

And success will also be reached when biases and negative stereotypes have been replaced with understanding and admiration.

Wokini is young, but vibrant.

We have strong support across our university community. Our governor, congressional delegation in D.C. and the leadership in our State Legislature have all been incredibly helpful.

Tribal leaders have also been supportive. Civic and business leaders across South Dakota are also very encouraging and supportive.

So how are we doing? At commencement last spring, for the first time in our university’s history, we began the ceremony with a land acknowledgement statement.

In 2017, we redirected the revenue from our Land-grant land and have spent $1.5 million on recruiting and supporting American Indian students in the last three fiscal years.

Our beautiful, new American Indian Student Center will open this coming spring.

The past two years, we have offered five-year, $5,000 renewable scholarships to qualifying American Indian students.

And I am excited to report that the retention rate of our first cohort was 80%.

We have raised over $8 million from gifts and grants from private individuals and foundations.

And, with the help of some of you, for which we are extremely grateful, we were successful in getting “New Beginnings” into the 2018 U.S. Farm Bill, which will annually provide up to $5 million in grants to Land-grant universities, and Tribal Colleges in support of American Indian students.

And there is more good news, as both the House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate have made appropriations to “New Beginnings.”

Of course, challenges remain.

We need a sustainable flow of resources to support scholarships. We need to institutionalize Wokini in order for it to be permanent.

And in order to better serve American Indian students and to assist in Tribal Nation building, we need to provide ongoing professional development opportunities for our faculty and staff to learn about the history, culture and current challenges of the Lakota and Dakota people.

However, we have come a long way in a relatively short period of time.

CONCLUSION

Because of Justin Morrill, William Henry Hatch and Seaman Knapp, like Archimedes, we have the power to lift the world.

We have so much to be proud of!

Those of us in this room make decisions on where we place our fulcrums in relation to our long levers of education, research and Extension each and every day.

We choose how much Land-grant force to apply.

We decide who and what we will lift up! What an awesome, exciting responsibility! Awe … but is it?

What if we don’t know and truly understand our own history?

What if we don’t acknowledge and respect communities different from our own?

What if we don’t apply the correct amount of force and leave a situation worse than where we found it?

What if we disregard a person, or people, for whatever reason who need to be lifted up?

What if we ignore aspects of the world around us that make us uncomfortable?

I understand.

But don’t forget C.S Lewis and his beautiful message of grace.

We can begin again and change the ending.

Can’t we?

Mustn’t we?

Will we?

Long ago, shortly before he was killed, the great Lakota Chief Sitting Bull challenged us, yes, all of us, with the following charge: “Let us put our minds together to see what life we can make for our children.”

I invite you all to join me in a Wokini, a new beginning, for all of our children.

Thank you for your time this morning. I am deeply humbled and greatly appreciative of this honor.