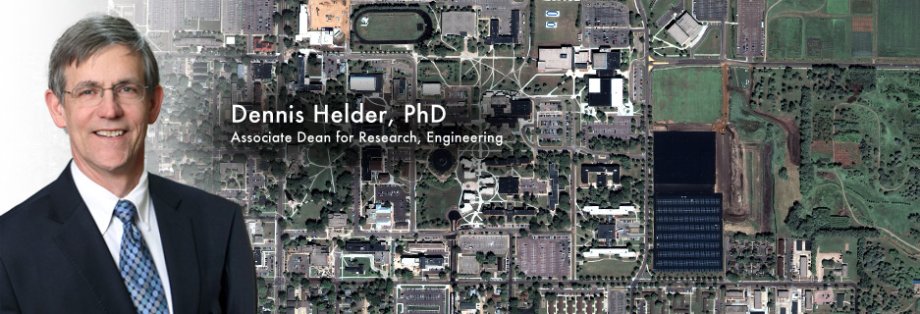

Retired researcher and faculty member Dennis Helder, of Volga, has been selected as the 2023 Distinguished Engineer at South Dakota State University.

Helder will become the 146th inductee into the Jerome J. Lohr College of Engineering’s list of Distinguished Engineers since Dean Junis O. Storry began the award in 1977. He will be honored at an April 26 engineering banquet at Club 71 in Dana J. Dykhouse Stadium.

Tickets for the Distinguished Engineers banquet are available from the dean’s office in the Lohr College of Engineering 605-688-4161. The tickets, which will be available until April 12, cost $20.

Helder was nominated by one of the 2022 awardees, Lew Brown, who served as dean from 2001 to 2018 and also nominated Helder for the rank of distinguished professor in 2012. The Distinguished Engineer nomination also was supported by two other previous Distinguished Engineers, Virgil Ellerbruch and Duane Sander, both of whom preceded Brown as dean.

Helder began work at SDSU as an undergraduate research assistant in 1978 and was on campus full time from 1983 until retirement in 2019, except for a brief sabbatical to earn his doctorate.

It was what Helder did during those 35 years that made him worthy of being a Distinguished Engineer.

Performed pioneering work for EROS

Helder's research career began with a cold phone call to the U.S. Geological Survey’s Earth Resources Observation and Science (EROS) Data Center near Baltic. That led to a career-long interaction with that facility and various NASA centers. His research focused on the radiometric calibration of optical remote-sensing satellites. Helder pioneered new methods that improved accuracy from a 15% error rate when he began to just over 1% when he retired.

Helder founded the SDSU Image Processing Laboratory in 1990. It is the oldest and most successful laboratory in the college and has an international reputation as an innovator in satellite calibration.

“Virtually every optical satellite in orbit bases its calibration on techniques developed by the IP Lab,” Helder said.

Helder became department head of electrical engineering in 2001. During his nine-year tenure, the department merged with computer science, initiated a software engineering program, achieved accreditation in both programs, initiated a doctoral program in electrical engineering and moved into a new facility—Daktronics Engineering Hall.

The department grew from 11 to 28 faculty members and more than tripled the number of students in graduate studies.

Preeminent in imagery calibration

Helder remains a world-class expert in the field of calibration and validation of satellite imagery and during his SDSU career brought in more than $27 million in research funding. “This is extraordinary and well above anyone else in the history of the Jerome J. Lohr College of Engineering and likely any individual ever at SDSU,” Brown said.

Brown noted that Helder’s expertise is recognized as such by NASA, EROS, the Department of Interior, Caltech’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and virtually all leading scientists and labs worldwide who are also involved in calibration and validation of satellite imagery.

In 2012, he was awarded the rank of distinguished professor, the first and only person within Lohr College of Engineering to be so awarded.

In 2004, the U.S. Geological Survey honored Helder with the John Wesley Powell Award, the highest civilian honor that the USGS can bestow. In retirement, SDSU awarded him the permanent title of distinguished professor emeritus of electrical engineering.

Not fully retired

So what has Helder done since retiring June 21, 2019, besides shoot whitetails, dabble in portrait photography and perform magic tricks for his 15 grandkids?

His business card says “senior technical adviser, engineering systems for KBR,” which is the Houston-based firm that contracts with the USGS for the operation of EROS Data.

“In a nutshell, I solve problems no one else has the expertise to solve,” said Helder, who also gave a deeper explanation.

“These are related to the calibration of optical remote sensing satellites (especially Landsat), atmospheric propagation, validation of surface reflectance products, estimation of bidirectional reflectance distribution functions, derivation of interoperability metrics, definition of uncertainty metrics for products, developing new approaches to all of these things and providing expertise on new satellite systems.

“I am also technical lead on a couple of projects. But, the best part is that I also mentor many of the young engineers in the EROS Cal/Val Center of Excellence, which I was tasked to develop when working part time for SDSU and EROS.”

Sounds like a full-time job for most folks, but Helder keeps a retiree’s perspective—working one day a week in the summers and two days a week in the winters.

Started as animal science major

It's not the career Helder planned. The Canton farm boy started out in animal science and did receive a bachelor’s degree in that in 1979. He also added a bachelor’s in electrical engineering in 1980 and worked as an undergraduate research assistant under Sander.

He worked as a radio frequency design engineer for E.F. Johnson Co. in Waseca, Minnesota, from 1980 to 1982 and then farmed in the De Smet area and operated Agritonics, his own two-way radio sales and service business geared toward farmers.

In fall 1983, Helder decided the time was right to add a master’s degree in electrical engineering. He also was working as a grad assistant on an electric tractor.

“I asked Dr. Ellerbruch, (head of electrical engineering then), if I could teach a class to see if I liked it.” He was assigned EE211, the foundation circuits class, not as a lab instructor but as classroom teacher. “I found I really liked teaching.” Ellerbruch also told him if he was going to stay in education, he needed a doctoral degree.

One book that changed his life

That meant he would need a doctoral dissertation.

So in fall 1988 as he searched for a topic, he recalled the book he’d seen on a colleague’s shelf in 1986 — “Digital Image Processing.”

“I looked at that book and thought this has got to be cool. I read it and thought, ‘My goodness. You can look at pictures as signals and process them as signals. That’s what I got excited about. It tripped my trigger,” Helder said in an earlier interview.

The next stop was EROS Data Center, where he met June Thormodsgaard, the image mapping and research development section leader. She gave Helder a problem that neither NASA nor EROS could fix. “The Landsat Thematic Mapper had started dropping scan lines. We were looking for a fix. There were people around the world that hadn’t been able to correct it,” Thormodsgaard said.

Using a university computer, Helder figured out an algorithm to remove lines, or bands, from satellite images of the Earth that were created by the camera.

So happy was Thormodsgaard with Helder’s work that she sent more assignments.

“I owe most of my career to that lady,” Helder said.

Meanwhile, the now-retired Thormodsgaard, said, “It’s a small, narrow group of people that have the expertise Dennis has. He didn’t need anybody. He just needed his hard work and his mathematical brain.”

- Contact:

- Telephone number: 605-688-4538

Republishing

You may republish SDSU News Center articles for free, online or in print. Questions? Contact us at sdsu.news@sdstate.edu or 605-688-6161.